A new state law intended to increase public awareness of sewer discharges into Massachusetts rivers hit an important milestone this week, producing data to help the public gauge how the Merrimack stacks up against other rivers where discharges occur.

The Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection released its first annual public report detailing sewage discharges into Massachusetts rivers, including the Merrimack and its tributaries the Concord and Nashua rivers. This new report was mandated by a law that Merrimack River Watershed Council and our fellow watershed conservation groups pushed hard to pass in 2021.

The report covers the period from July to December 2022 — covering only half the year, because the law took effect on July 1. In future years the reports will cover full calendar years.

Combined sewer discharges, known as CSOs, have been occurring on the Merrimack for decades, but in the past few years they have attracted significant attention. In 2018, a series of large CSO events drew substantial media coverage and public backlash, with much attention focused on the fact that the state had no laws mandating that sewer plants alert the public when sewage is released.

Raw sewage in rivers is known to contain bacteria that can be harmful to people and wildlife who come in contact with contaminated water.

Public and media attention culminated in the passage of the law, which requires sewer plant operators report discharges to the public immediately, and to collect and file data to the state DEP,

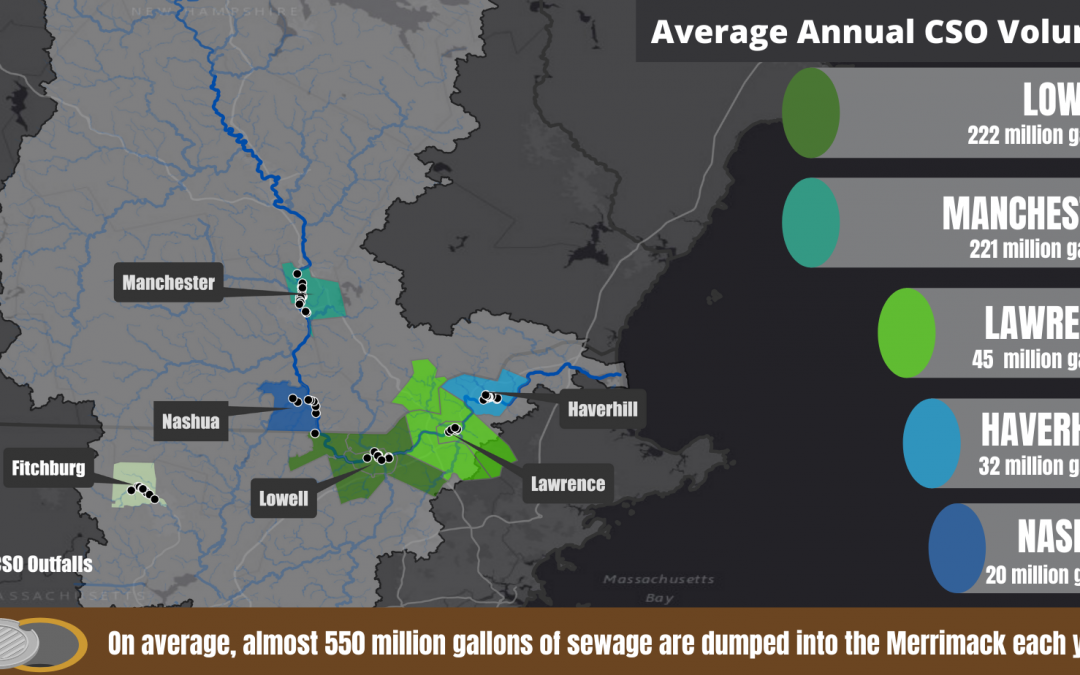

On the Merrimack River, five public sewer systems — serving Haverhill, greater Lawrence, and greater Lowell in Massachusetts, and Nashua and Manchester in New Hampshire — release raw sewage into the Merrimack, typically after large rainstorms. In an average year, 540 million gallons is released from the 5 plants.

The new DEP report delves into the details of CSOs and other events in which sewage seeps into Massachusetts rivers. Among the report’s highlights:

Statewide, some 1.44 billion gallons of untreated and partly treated sewage was discharged from sewer plants from July-December 2022. The river with the largest volume was the Connecticut (381 Million Gallons), followed by the Merrimack (311 MG). The third highest discharge was reported on the South Shore, at Mount Hope Bay (197 MG). There are also 4 smaller rivers along the Merrimack — Little River in Haverhill, Beaver Brook and Concord River in Lowell, and Spicket River in Lawrence — where sewer discharges occur very close to where these rivers flow into the Merrimack. If the discharges from these rivers are added in, the Merrimack’s total volume increases to 342 million gallons.

The river with the most number of days in which a sewer discharge event occurred was the Connecticut, with 47 days during the 180-day period of the report. The Merrimack had events on 21 days, the 8th highest of the 29 rivers and waterways where sewer discharges occur.

The largest volume produced by a single sewer plant in the state was Lowell, at 318 million gallons. This includes both partly treated and untreated sewage. The next highest was Fall River at 277 MG, then New Bedford at 230 MG.

In Massachusetts, there are 19 communities that are permitted to discharge sewage into public waterways. Under state and federal laws, all of them are required to eventually end this practice. The financial cost of ending sewer discharges is high — estimated to be $1 billion on the Merrimack River alone. This is because miles of sewer and street drain pipes must be redesigned, dug up, separated and replaced. The process takes years.

The year 2022 was a drought year, and so CSO volumes were lower than in an average rainfall.

To view the full report, click HERE.

Recent Comments