Combined Sewer Overflows (CSOs)

Post-CSO Testing Program

WHAT IS A COMBINED SEWER OVERFLOW (CSO)?

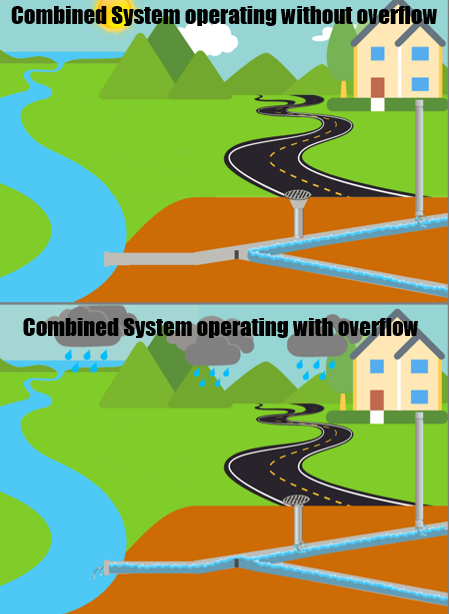

A combined sewer system collects rainwater runoff, domestic sewage, and industrial wastewater into one pipe. Under normal conditions, it transports all of this water to a sewage treatment plant for treatment, then discharges to a water body. When the system works correctly, it is best for the environment and our water bodies, as stormwater as well as wastewater gets treated. However during heavy rainfall and snowmelt, the volume of combined storm and wastewater can exceed the capacity of the system or treatment plant. When this occurs, untreated stormwater and wastewater discharges directly to nearby streams, rivers, and other water bodies rather than backing up into homes and businesses. This is a combined sewer overflow (CSO).

CSOs contain untreated or partially treated human and industrial waste, toxic materials, and debris and stormwater, which may include harmful bacteria and pollution. They are a priority water pollution concern for the nearly 860 municipalities across the U.S. that have combined sewer systems.

Overflows in the merrimack

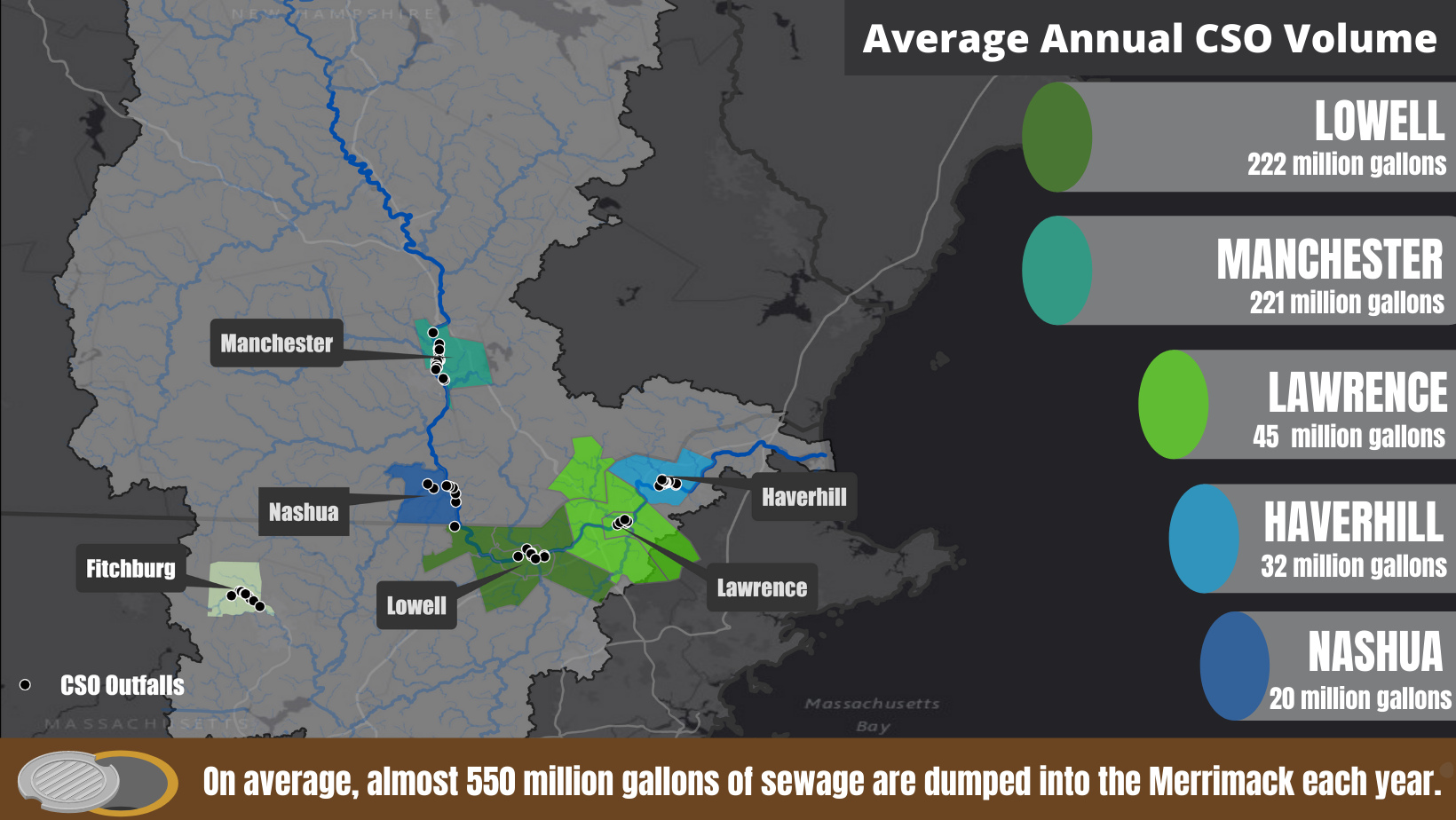

Six urban sewage treatment systems in the Merrimack River watershed frequently discharge CSOs during rainstorms. On the mainstem Merrimack River: Manchester and Nashua in New Hampshire, and Lowell, the Greater Lawrence Sanitary District (GLSD), and Haverhill in Massachusetts. Fitchburg, MA also discharges into the Nashua River, a tributary of the Merrimack. These sewage treatment plants are under government order to eliminate most of their CSOs, but without additional federal and state funding, it may still take several decades to get there.

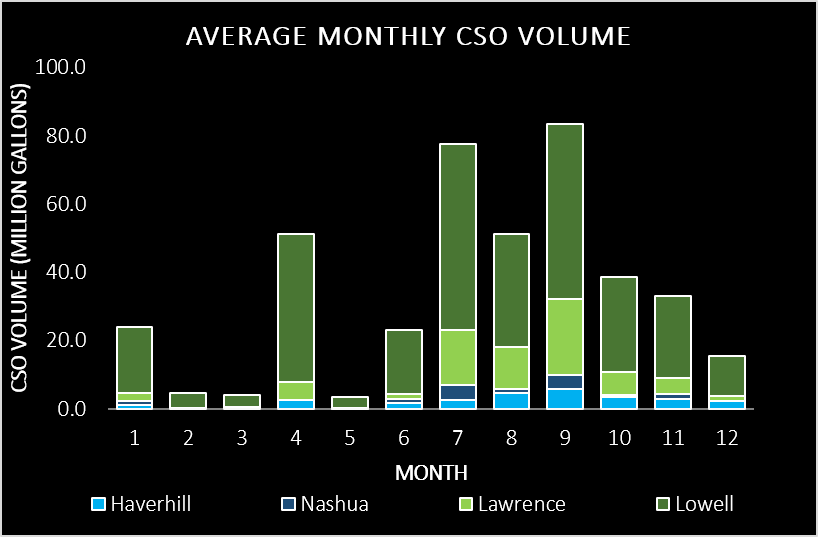

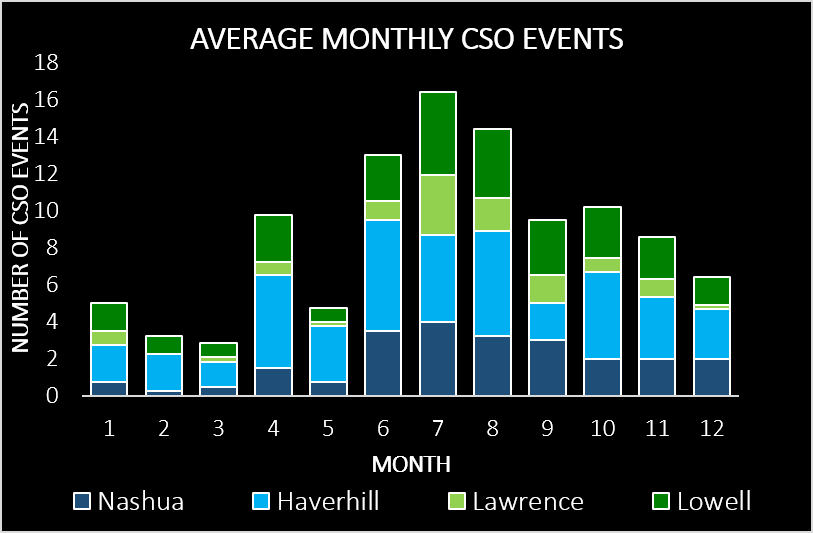

All data are sourced from annual reports from each wastewater facility. Monthly CSO data are averaged from 2018-2021 for all plants except Haverhill as 2021 data were not available at the time this was prepared. Data do not include Manchester as individual event data are not reported by Manchester.

All data are sourced from annual reports from each wastewater facility. Monthly CSO data are averaged from 2018-2021 for all plants except Haverhill as 2021 data were not available at the time this was prepared. Data do not include Manchester as individual event data are not reported by Manchester.

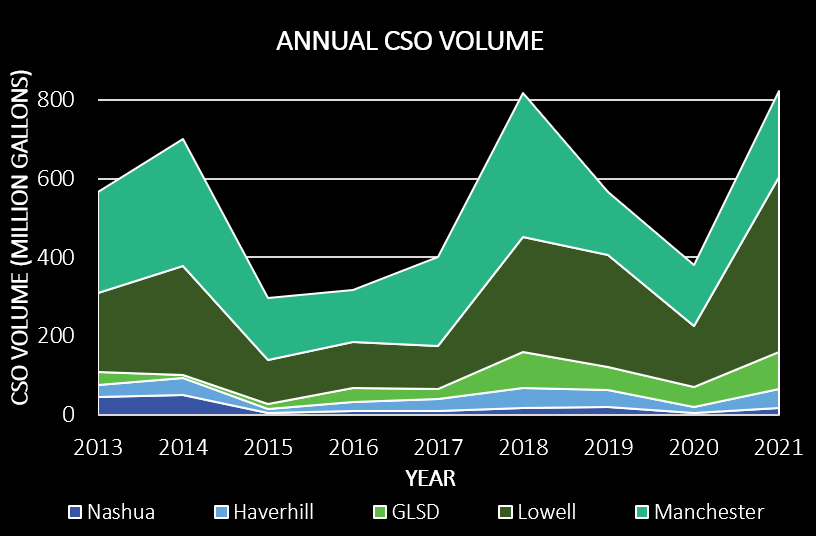

All data are sourced from annual reports from each waste water facility. Data for Haverhill in 2021 are estimted as the 2021 report was not available at the time this was prepared.

watch the 8-minute explainer about sewage in the Merrimack

What we are doing to fix the problem

Access to Information

In 2021 Massachusetts passed a major piece of legislation to begin the end of CSOs—the “Act promoting awareness of sewage pollution in public waters”. This bill, finally requiring sewage plants to tell the public whenever sewage is released into the river, was a result of years of tireless efforts by MRWC and partner organizations. Read more here.

MRWC’s campaign to bring the sewage dumping issue to the public’s attention has generated tremendous response. Thousands of people have commented on or shared our posts on social media, and many have called their local legislators, written letters to their local newspapers, and volunteered to help spread the world. This and coverage by local media has fueled a variety of actions by elected officials and resulted in federal lawmakers identifying funding sources. This is a significant development. We’ll be closely tracking progress.

Water Sampling and Data Analysis

Our water quality monitoring program monitors bacteria levels in the river under baseline conditions and following CSO events.

Not all CSOs are equal – some facilities like Haverhill have small but frequent events, others like Lowell have less frequent but very large events. Differing conditions means differing risks to people downstream. We compare CSO data from the wastewater treatment facilities with our water quality monitoring data to better understand the risk that CSOs pose to downstream communities.

Long Term Solutions

CSO operators should upgrade their systems as soon as possible. We are encouraged that all 5 plants on the Merrimack mainstem are voluntarily notifying the public when CSOs occur. Over the past few years, Lowell has decreased their contribution of CSOs significantly. Across the state, many plants have joined a coalition pushing for federal money to pay for the improvements needed to end CSOs.More work is still needed. Some facilities may require a fully separated sewage and stormwater system. This option is very costly, disruptive to residents and leads to untreated stormwater flowing into the rivers, including pollutants and bacteria. Others may be able to use storage solutions, or green infrastructure. We are working alongside wastewater treatment facilities and policy makers to advocate for solutions tailored to each system’s situation. State and federal funding is necessary for CSO elimination. We are hopeful that new infrastructure funding will support long term solutions.

What you can do to fix the problem

Conserve water

Use less! The less water going through the system during rainstorms, the better! From less laundry to fixing your leaky faucets, from rain barrels to redirecting your downspout.

Keep Water Clean

Wash your car at a commercial car wash rather than at home, Pick up your pet waste. Minimize fertilizers and pesticides in your yard. Maintain your septic tank. Purchase eco-friendly household detergents and cleaners. Be sure to dispose of used oil, antifreeze, paints and other household chemicals properly—not in storm sewers or drains.

Support Local Champions

You vote with your dollar. The Merrimack River Watershed Council is just one of the local groups working day in and day out for a healthy environment and a just society. Consider a donation.

Use your voice

Get your elected representatives on speed dial! Write letters to your local newspaper, post your opinion on social media, and help educate friends and family. And VOTE! Elections matter.

Manage your stormwater with native plants

The more stormwater (runoff) that infiltrates into the soil, the less likely a CSO will occur. Install native plants, plant more trees and consider a rain garden, a green roof, or permeable pavement.

Learn More

How to stay informed about CSoS

Four watewater treatment plants — in Haverhill, Lowell, Lawrence, and Manchester — provide reports whenever there is a CSO. The Nashua wastewater plant is required to post alerts on the city’s website page. As of now, there is no centralized system to subscribe in order to receive alerts from all plants, but you can sign up for their notifications individually:

- Haverhill: Email csoalert-sub@haverhillwater.com, view real time information here

- Lawrence: Sign up here

- Lowell: Sign up here

- Manchester: Sign up here

- Nashua: You can monitor the city’s wastewater facility website during and after storm events for information

We should note that the emails from the plants are not always easy to understand, and each plant reports its CSO event differently. For instance, Lowell sends out 3 alerts — one when the CSO begins, one when it ends, and a follow-up a few days later reporting how much sewage was released. Haverhill and Manchester send out one email that links to a map of where discharges have occurred, when they started and ended, and how much volume was released. Greater Lawrence sends emails at the start and end of a CSO release, and several days later reports the volume released.

Download CSO Data

Each wastewater treatment plant on the mainstem of the Merrimack has a different system for sharing data with the public. In addition to receiving notifications as CSOs are occurring, you can also download data about past CSO occurrences.

- Haverhill: Visit Haverhill’s website and scroll to the bottom of the page to download annual reports these are updated once per year.

- Lawrence: Visit Lawrence’s website and scroll to the middle of the page to download reports. Lawrence updates this information multiple times a year.

- Lowell: Visit Lowell’s Document Center, click the “Public Works” folder, then “Wastewater Utility”, then “Resources” to find quarterly reports.

- Manchester: Manchester does not yet have a system for downloading CSO data.

- Nashua: View Nashua’s report. Volumes are updates multiple times a year.

How Bacteria is transported in the river

Rivers are living, moving systems, which means, unfortunately they are a conduit for transporting bacteria from CSO outfalls to other areas of the river downstream Additionally, there are a lot of bacteria contributions to the river from sources other than CSOs, and other pollutants apart from bacteria that contribute to poor water quality in the river

- Other pollutants may include nutrient pollution from farms, legacy industrial pollution in river sediment, storm runoff that doesn’t trigger a CSO but still contributes direct runoff containing bacteria, animal defecation in the river and general trash and other things that are dumped into the river or wash into it when it rains

- This can be particularly exacerbated when it rains after droughts, which is an issue we are seeing more with climate change

While CSOs are a major problem where they occur, natural processes occurring within the river may mitigate the bacteria concentrations as they move downstream- not all CSOs mean the river is unsafe everywhere, and the risks may be delayed in downstream communities. Communities close to the outfall will be affected during and directly after rain events. People downstream may be affected later, less severely affected, or not affected at all.

The connection between when and how large a CSO event is, and when and how serious the health concern in the river is complex, and is impacted by:

- Streamflow: How fast the river is moving determines how fast and how far the bacteria will move downstream. When flows are low, other processes may eliminate the bacteria before it makes its way all the way downstream. When flows are high, the bacteria may move downstream faster than it dies off

- Dispersion: The bacteria plume will be concentrated at the outfall, but will disperse in the river in depth and across the river once it starts mixing.

- Dilution: As soon as the bacteria is contributed into the river, it’s concentration is diluted by the river water.

- Decay/die off: Bacteria are living beings that do not exist and live forever. Their die off rates can be impacted by temperature, sunlight, dissolved oxygen, salinity, existing bacteria concentrations in the river and more.

- Tides push pollutants up and downstream, but also incoming seawater may dilute concentrations or affect die off rates due to high salinity. Tides affect the Merrimack all the way to the Essex Dam in Lawrence.

How this affects you

Sewage can remain in the Merrimack for days after a CSO event—a period during which, in many cases (especially in the nice weather), the skies will have cleared, leaving the river environment deceptively inviting to anglers, boaters, swimmers, and other recreational users of the river. Before you visit the river for recreation, consider how long ago a CSO occurred.

Exposure to raw sewage can cause multiple, serious health problems, particularly for the very young, the elderly, and those with compromised physiology. According to EPA, raw sewage includes disease-causing agents falling into three general categories:

- Bacteria: single-celled organisms that, when pathogenic, can cause cholera, dysentery, shigellosis, and typhoid fever;

- Viruses: parasites that grow on living tissue and, when associated with feces, include hepatitis A, Norwalk-type virus, rotavirus, and adenovirus; and

- Protozoans: about a third of all protozoans are pathogenic, and these can cause gastrointestinal disease, dysentery, and ulceration of the liver and intestines.

A 2015 peer-reviewed health study that included the Lawrence area along the lower Merrimack found a statistically significant association between heavy rains (which trigger CSO events) and an increase in hospital emergency room admissions of people complaining of gastro-intestinal disorders.

Nearly all of the sewage from CSOs is discharged upstream of drinking water plants that provide Merrimack River water to residents in six municipalities: Lowell, Lawrence, Methuen, Andover, North Reading, and Tewksbury. (A sixth, Nashua, receives about a quarter of its drinking water from the river.) All told, more than 600,000 people get their daily drinking water from the Merrimack River. Within a decade, that number is likely to increase, as Manchester and Haverhill tap into the river to expand local supplies and sell water to other communities.

The Merrimack River is the second-largest surface-based drinking water source in New England. The largest is the Quabbin Reservoir, which, unlike the Merrimack, was built to provide pristine drinking water to Eastern Massachusetts. Drinking water is heavily treated and it is unlikely water coming out of the tap from city supplied water will be contaminated with bacteria. A study by the US Geological Survey did not find contaminants at reportable levels in treated drinking water, despite finding some in source water on the Merrimack, suggesting that water treatment methods are working correctly to eliminate contaminants from CSOs in drinking water. Even still, polluting our drinking water sources is a major concern.

How this is allowed

Much of New England’s infrastructure is old and was not designed for the volume of rain runoff that takes place during even short duration storms. As populations grew, the amount of impermeable surfaces (examples include buildings, paved roads and anything preventing water from infiltrating into the ground) expanded, increasing the amount of stormwater runoff. Even with upgraded wastewater treatment plants, they can easily reach capacity leading to runoff into the Merrimack River. The system is working as intended when it combines raw sewage and stormwater runoff.

The fix is not an overnight one. It is expensive and would take several years to dig water lines and separate the storm water piping from the sewage piping. Factoring in that water pipes are generally working due to gravity alone, they tend to be some of the deepest utilities underground and are often buried under other utilities. Because of all this, the sewage plants are authorized to dump sewage in the river under these circumstances for the time being.