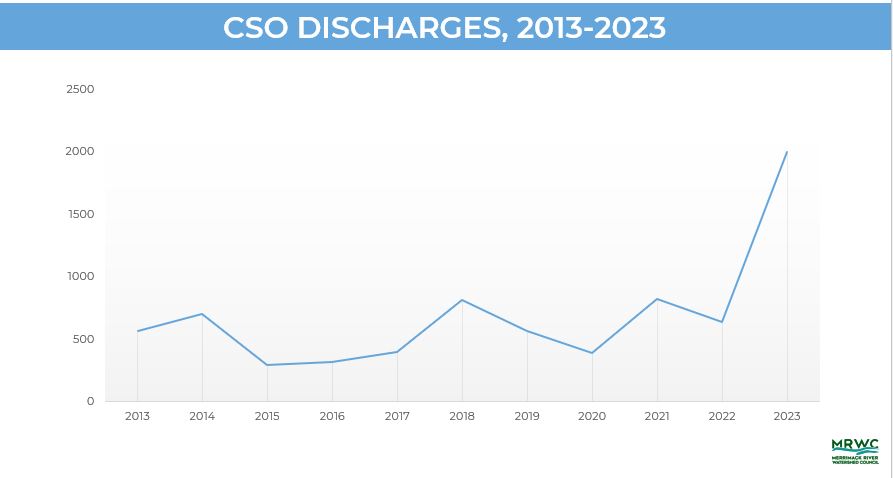

MERRIMACK RIVER – The huge rainstorms that hit the region in 2023 triggered a record-setting volume of sewage discharges into the Merrimack River, according to data obtained by Merrimack River Watershed Council.

Just over 2 billion gallons of Combined Sewer Overflow – raw sewage mixed with runoff from urban street drains – were discharged into the river from five cities along the Merrimack. The previous record, set in 2021, was 823 million gallons.

The largest flow came from Manchester (875 million gallons), followed closely by Lowell (850 million gallons). Between them, they accounted for 86% of the total volume. The others were Greater Lawrence (164 million gallons), Haverhill (97 million gallons estimated), and Nashua (20 million gallons).

MRWC’s records go back to 2013, the first year that CSO data from all 5 plants became publicly available. In an average year, about 550 million gallons of CSO waste is discharged.

“The enormous amount of rain we received last year was the primary reason why we had such an astonishingly high volume of CSO waste discharged into the river,” said John Macone, MRWC’s policy and education specialist. “I heard many complaints and concerns from people throughout the region about the unhealthy appearance of the river last year, and the new data helps to verify that we experienced an unusual bad year for CSO events.”

“Climate change scientists have been predicting that the Northeast will witness a substantial increase in heavy rainstorms, and in 2021 and 2023, we certainly saw that in the Merrimack Valley,” said Macone.

CSOs can contain high levels of harmful bacteria that can cause rashes, infections and intestinal problems for people and animals that encounter it. CSOs can also be harmful to fish due to reduced oxygen levels. As a rule of thumb, the state Department of Health advises people to avoid direct contact with river water for 48 hours after CSO events occur.

June and July were particularly tough months on the Merrimack. Of the 61 days in those months, the river was under “no contact” CSO-related advisories for 39 days.

CSOs occur in many industrial cities nationwide that boomed in the 19th century through mid 20th centuries – during a time when it was common practice to combine sewer and drain pipes and discharge their flow into rivers. At that time, there were no sewer plants.

Since the late 1970s, sewer plants have been mandated and built, and they are able to process all of the sewage generated in a typical dry day. But the volume that flows into the plants during rainstorms overwhelms their ability to process it, and so excess flow is discharged into the river.

The solutions are expensive – most common is digging up streets and separating the pipes, building underground storage tanks, and expanding treatment plants.

Currently, both Lowell and Manchester are embarking on massive projects that will reduce their CSO volumes.

In Manchester, a $300 million project is underway. One of its key components is digging a 2-mile-long tunnel to separate stormwater and sewage. The tunnel is deep – up to 80 feet underground in some spots. When finishes, it is expected to reduce the city’s CSO outflow by 80 percent.

In Lowell, the city recently agreed to an EPA legal order to spend about $200 million to reduce its CSO output through a largescale pipe separation project. Lowell will also fix problem spots where sewage is discharging into streets, yards, and basements. Lowell’s plan is still being worked on and the initial construction is expected to start in 2025.

Merrimack River Watershed Council is working with Massachusetts legislators and officials, and the planning agencies that serve greater Lowell (NMCOG) and greater Lawrence/Haverhill (MVPC) to pass legislation that will create a new regional collaborative focused on problems that impact the river. One of the goals of the group will be to help Merrimack River communities understand the financial challenges that Lowell faces with its CSO project, and work together to help Lowell secure the state and federal funding it needs.

“We’d like to do as much as we can to reduce the financial burden on Lowell residents,” said Macone. “This is an issue that impacts the river from Lowell to the sea, and if we can work together as a region we will have more clout and success.”

MRWC has also been awarded funding by the Massachusetts Legislature and state Department of Environmental Protection to help develop regional solutions to the Merrimack River’s CSOs. That funding will go toward a variety of projects aimed at providing new scientific data about Merrimack River CSO events, investigating new technology for improved bacteria testing, and outreach.

Recent Comments